Robots are beginning to encroach into the human workplace in ways never seen before. Humans are being displaced out of work, and it is increasingly looking like we have no plan. Why is this happening? And what can be done about it?

The term, automation, was coined in 1946 to describe the increased mechanisation of automobile manufacturing, spurred on by the booming postwar economy. The basic principle behind automation, however, has existed for thousands of years, where humans have found ways to complete tasks with reduced human assistance. By using the current of rivers in waterwheels or the flow of wind in windmills, our species has adopted many ingenious methods throughout history to lessen the work on our shoulders.

With the advent of steam power in the 19th century, this was expanded upon greatly and ushered in the Industrial Revolution. Using new technologies, humankind experienced an unprecedented growth and expansion.

Over 100 years later, we stand on the precipice of another industrial revolution.

What’s going to happen?

It’s already begun. All around us, in little ways, our world is beginning to be transformed.

About ten years ago, self-checkouts began being rolled out across supermarkets, leading to a drop in the number of employees needed at any supermarket branch with them. This rather aptly demonstrates the threat levied by automation. From a purely capitalistic point of view, it makes sense to replace workers with machines. Machines don’t need a salary, don’t get sick and can work every hour of every day. In the USA, 140,000 jobs were lost in the retail sector between January 2017 and March 2019 and automation was a major contributor.

If anything, however, the rise of self-service checkouts is merely a drop in the ocean of what’s to come. Almost every industry will be affected.

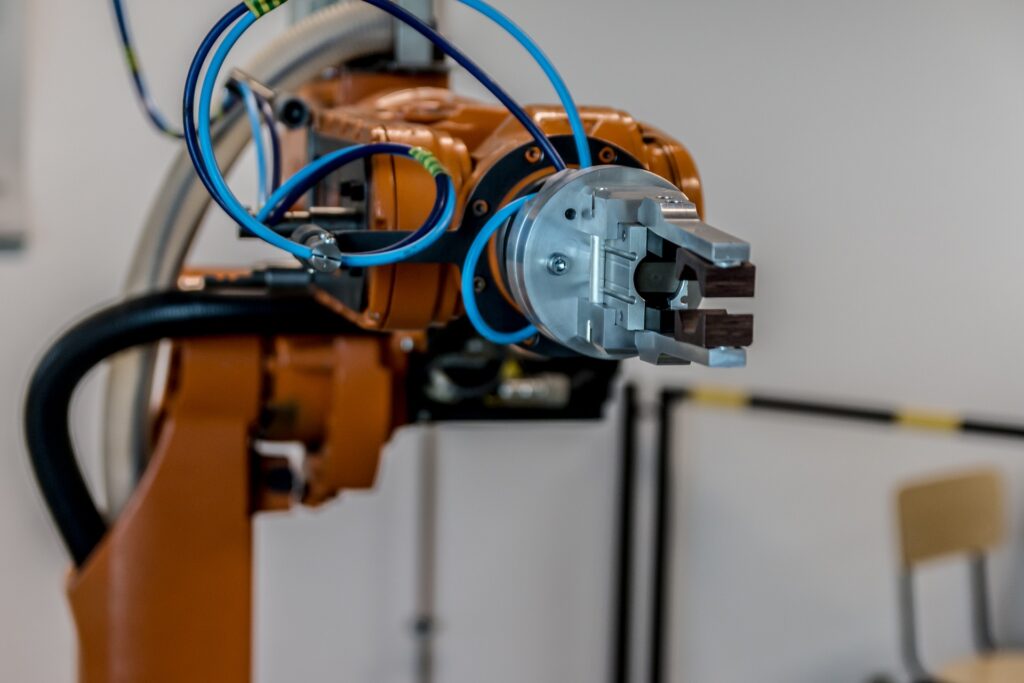

In industry and production, so-called ‘smart factories’ will be possible. These will be almost completely autonomous, streamlined factories where hundreds of robots work seamlessly together to create a massive variety of materials and goods.

But it doesn’t just stop there. Smart farms – where a number of sensors, satellites and detectors can be deployed and work together to optimise crop yields – are just one example of how this technology will change all our lives. Using artificial intelligence (AI) and autonomous machines Some are hoping that this may serve as a solution to the upcoming food crisis as the human population continues to skyrocket.

The COVID-19 pandemic has just sped things up. As social distancing becomes the norm for the next few years, humans will more readily rely on machines to bridge that gap. In Belgium, companionship technology has been used in care homes to ensure those isolated don’t become lonely. Using Zorabots”, family members can communicate with relatives through video feeds, mounted on top of 1.2-meter-tall mobile robots.

In Singapore, parks have deployed a ‘robot dog’ that enforces social distancing. They detect how busy the park is and is fitted with a loudspeaker to announce social distancing measures.

South Korea, a world leader in robotics, has seen the deployment of robot baristas. These robots can take an order, produce the drinks and bring it to the table completely autonomously; it can also produce 60 different types of coffee. It is this kind of technology that will be accelerated by Coronavirus. With an increased need to socially distance, it makes sense for this technology to be more widely adopted.

What’s fuelling the change?

There have been several paper’s researching the causes of the rise of automation. Lasi et al. – in 2014 – described it as a push/pull effect. They stated that simultaneously the industry was being forced to change (the push) and technological innovations were making it easier (the pull).

Some specific push factors include the dawn of the ‘sellers’ market’ and increased demand for individualisation of products, the increased expectation of flexibility in companies and the need for resource efficiency.

Some push factors include the increased mechanisation and automation of technology, the digitisation and networking that has come about in the last 10 years and miniaturisation of technology.

Who will be affected?

In 1966, the sociologist William Silverman concluded that automation ‘reduces employment in organisations’. Over 50 years on, he is still correct. Massive social upheaval is posed to take place, yet few seem to be paying attention. This will disproportionately affect the most vulnerable in society; those on the poverty line.

Specific projections for the effects on employment numbers vary. According to a report by the PwC, a professional services company, 30% of all jobs could be automatable by the mid-2030s, with the transport and finance sectors being the worst affected.

The outlook gets even grimmer.

12% of all ‘high-educated’ jobs, 25% of ‘median-educated’ jobs and a massive 47% of ‘low-educated’ jobs (GCSE or lower) will be automatable.

It may not be so black and white though. A report by the Boston Department of Economics says that labour is ‘reinstated in new activities’. The money that was being paid to an employee in a now-redundant job can be used to create higher-skilled jobs – it can drive employment. However, people will still be adversely affected if governments aren’t careful – they must be ready to provide the proper support networks to retrain people put out of work.

What will change?

The rise of far-right nationalism across the Western world has been partially attributed to automation. Since the dawn of the 21st century, political parties such as the UKIP in the UK, the AfD in Germany and the National Rally in France have witnessed an unprecedented rise.

This is poised to increase even more if nothing is done about automation.

A paper, published in 2019, observed 11 West European countries and tried to characterise the association between automation and vote choice. It describes the upcoming redundancies as a ‘reservoir of votes for the radical right’.

This phenomenon occurs because the groups most threatened by automation are also most receptive to the narrative used by the radical right. It is possible that this will have enormous international implications in the next 10 years.

However, not everyone is ignoring this.

In the 2020 US Democratic Party primaries, a longshot progressive candidate called Andrew Yang caught the spotlight when he based large parts of his platform on responding to automation. He blamed the rise of Donald Trump on automation and even suggested policies to mitigate the negative effects of it. Whilst he dropped out early into the primaries, he played a significant part in bringing automation into political discourse.

This is a huge, world changing issue and has the potential to cause massive unrest. But it is also a chance to improve everybody’s lives, increasing convenience and ease for everyone.

What happens next is up to humanity.