In archaeology, experts use many different forms of analysis to learn about the Earth’s past. One of these methods is known as isotope analysis. By characterising the elemental makeup of human remains, we can determine qualities like their age or diet.

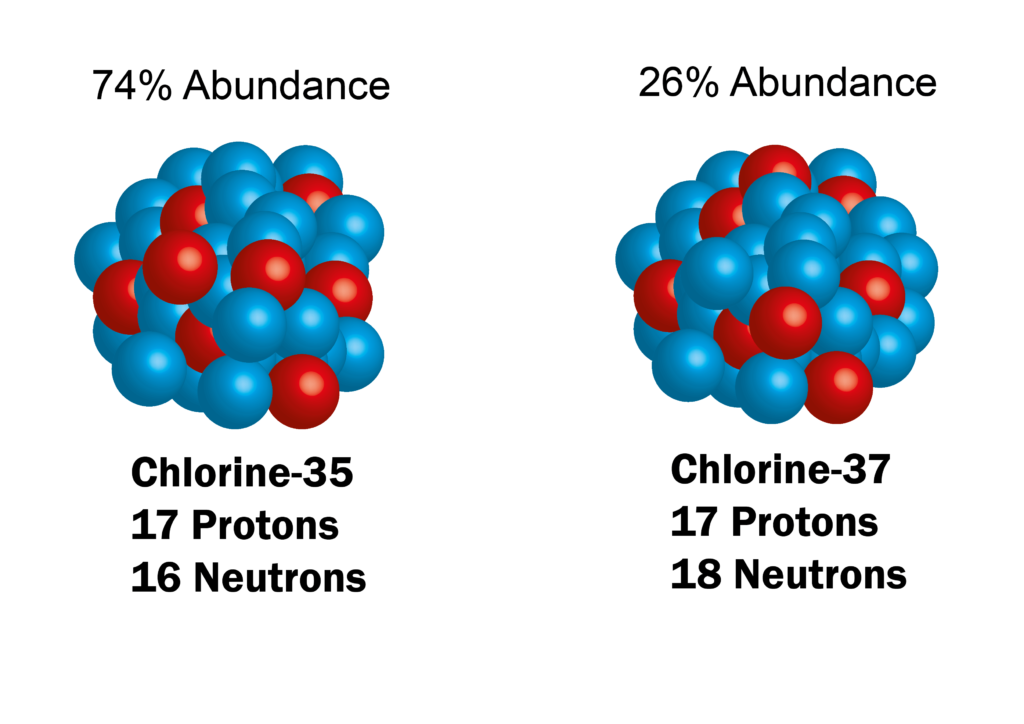

Atoms of an element do not have a single mass. There are usually many different varieties of a single element – all with slightly different masses – called isotopes. For example, take the element, chlorine. On the periodic table, it displays a mass of 35.5. This doesn’t mean a chlorine atom weighs 35.5, it refers to the fact that there are two stable isotopes of chlorine. One has a mass of 35 and one has a mass of 37. A weighted average – using the abundance of each variety – is used to give the overall mass of 35.5.

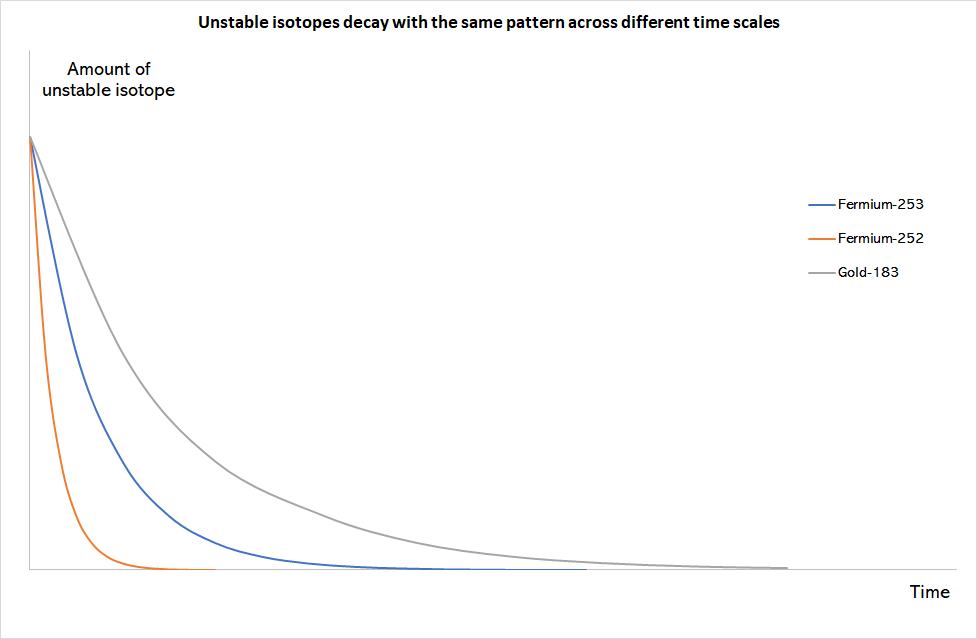

Some isotopes are not stable. If an isotope is too heavy, it can fall apart spontaneously to form a more stable atom through a process called decay. It stabilises by ejecting part of it’s mass and releases energy in the form of radiation.

The amount of an unstable isotope can be used to date human remains. A common way to do this is by using a method called carbon dating.

Carbon-14 is an unstable isotope of carbon that decays into nitrogen over thousands of years. It’s formed in the upper atmosphere when cosmic rays collide into nitrogen. As a result, trace amounts of it exists in the air as CO2. This is naturally consumed by plants via photosynthesis and then by humans when they eat the plants. The carbon is then incorporated into bones via natural bodily functions.

Whilst living, the amount of carbon-14 in humans stays at roughly the same level; upon death, they stop consuming it and the amount of carbon-14 begins decreasing as it decays. Since carbon-14 decays at a known rate, archaeologists can determine how old something is by looking at how much of it there is left.

Isotopic analysis can also be used to investigate the diets that animals and humans had.

One way to do this uses Carbon-13, a stable isotope of carbon. There are two subsections of plants, C3 plants and C4 plants. C3 plants include most land plants like fruits and nuts. Whereas C4 plants notably contain maize, rice and sugarcane. Both varieties have different ratios of Carbon-13 to Carbon-12 due to slightly different methods of photosynthesis. Therefore, the predominant diets of any given human can be worked out by measuring the Carbon-13/Carbon-12 ratios in bones.

Because C3 plants have less Carbon-13 in them, bones of a human that had a C3 plant-rich diet will also have less Carbon-13 in them. Similarly, remains of a human that had a C4 plant-rich diet will have more Carbon-13 in them.

This has been used to track the spread of agriculture across North America around 1000 AD; maize – a C4 crop – was the predominant crop used by native farming communities.

Used in tandem with isotopic nitrogen analysis, it has also been used to shed light on how different communities traded food along Central Asia’ Silk Road. They found that nomadic communities had higher variations of isotope ratios in their remains, indicating trade activity occurring between them. In contrast, they found that urban communities had low isotopic variation, implying that they relied on more localised food production.

Love this, the provenancing potential of the application of isotope science in archaeology is unlimited, literally the forefront of the discipline of archaeological science.